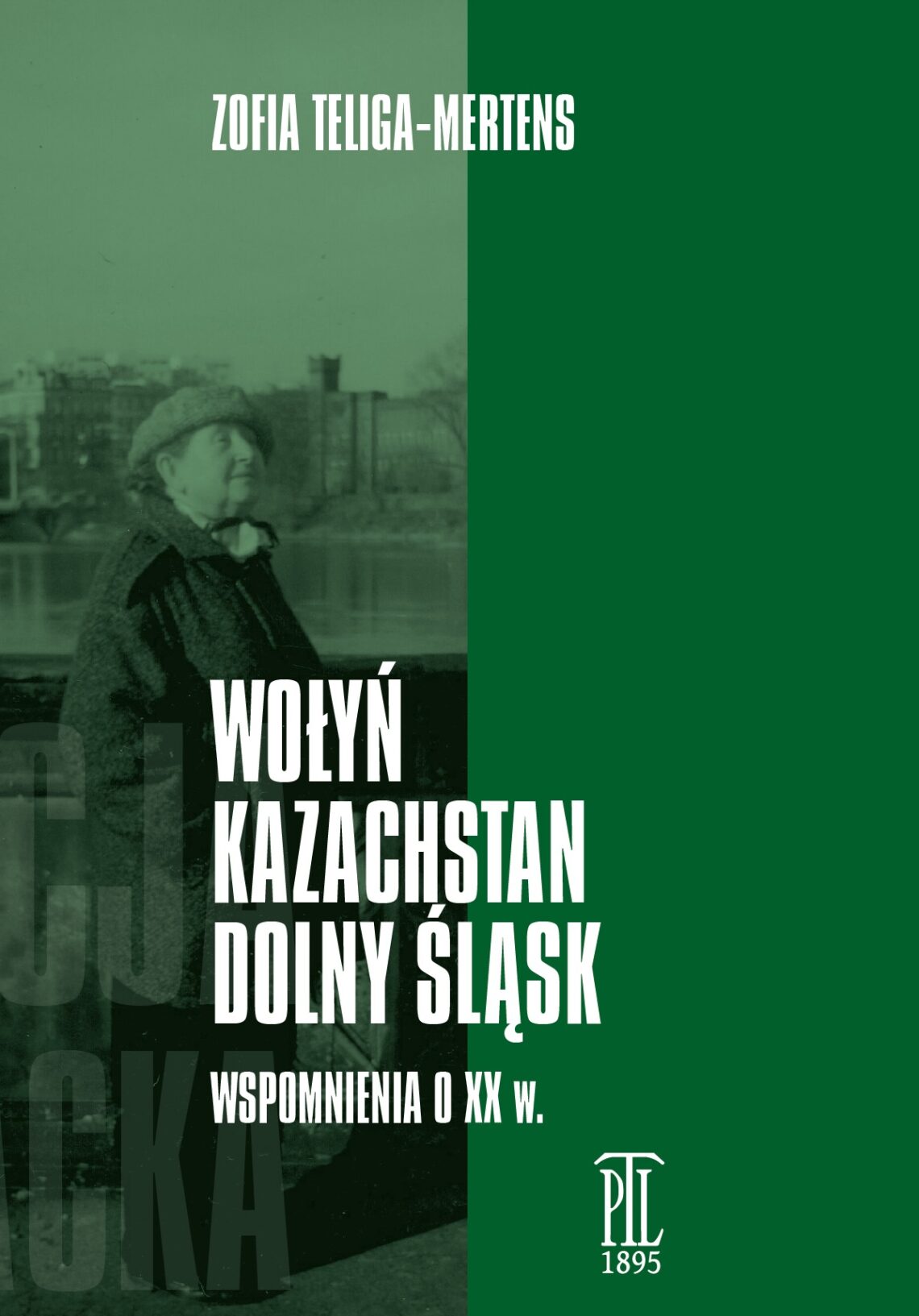

Zofia Teliga-Mertens (1926-2022) lived before World War II in Volhynia, in eastern Poland. Her father, Stefan, was an officer in the Polish army. He was given farmland there for his services during the struggle for Poland’s independence. Her mother, Zofia, came from the Polish-Czechoslovak border region. The couple met in Kielce. After their wedding, they settled in Wola Rycerska near Krzemieniec (Kremenets), where Zofia Jr. was born. This part of pre-war Poland was dominated by the Ukrainian population, which constituted about 70% of the residents of the Volhynian Province. Through hard work and sacrifice, the young couple transformed the land assigned to them into a well-functioning farm. On a daily basis, the author’s mother managed it, in this way supporting her husband’s social activities, which took up a lot of his time. The Teliga family belonged to the folk movement, which was in opposition to the state authorities. The father had no class or national prejudices and was open to contacts and the needs of their Ukrainian neighbours.

The attitude of her parents, both in terms of work ethic and their socio-political views, strongly influenced Zofia. Even as a child, she showed great independence, curiosity about the world, and sensitivity to poverty and human suffering. She enjoyed visiting various homes in the area, not confining herself to the circle of residents in the military settlement. From a young age, she set life goals for herself—she wanted to become an agriculture specialist and work in the poorest rural areas.

In 1938, having completed primary school, Zofia began her studies at the gymnasium in Kremenets. The outbreak of the war interrupted her further education. Volhynia was annexed by the Soviet Union. The Soviet authorities confiscated the Teliga family’s farm and deported its owners, along with 140,000 Poles, deep into the USSR in February 1940. The Teligas ended up in the Arkhangelsk region, in a settlement in the taiga. The main type of forced labour there was logging. The author’s father’s health, which had not been good even before the war, began to deteriorate rapidly. After the outbreak of the Soviet-German war and the so-called amnesty for repressed Polish citizens in the autumn of 1941, the Teliga family moved south in search of better living conditions. On their way to Uzbekistan, Stefan got separated from his family. As his wife and daughter later found out, he became seriously ill and died in the hospital in Kokand in mid-February 1942. Both Zofias were in the South Kazakhstan Oblast at that time. The death of her father and her mother’s serious illness meant that fifteen-year-old Zosia had to grow up quickly. After some time, the two Zofias settled in Turkestan. The author’s mother ran a Polish orphanage there until the resumption of Polish-Soviet relations was severed again in April 1943. The author’s mother was removed from the Turkestan facility, where the Polish staff was replaced by Soviet personnel. Zofia Jr. worked hard in a sovkhoz.

In the second half of 1943, under the patronage of the Union of Polish Patriots (Związek Patriotów Polskich, ZPP), a recently established organization led by the communists, a school was opened in Turkestan. The author attended it for a relatively short time. Besides that, she helped her mother with her work in the local structures of the ZPP. In the summer of 1945, her mother was appointed head of the Family Search Department of the Main Board of the ZPP in Moscow. By that time, the Kremlin had agreed to repatriate Polish exiles back to their homeland. While waiting for their departure, Zofia began self-education, dreaming of studying agriculture.

Zofia and her mother arrived in Poland only in July 1946, at the end of the mass repatriation from the USSR that affected almost a quarter of a million people. After a short stay with relatives, they settled in Wrocław, a city that was unfamiliar to them and severely damaged, but offered the chance to finally achieve some stability in their lives. Her mother worked as a clerk, while Zofia studied at the Faculty of Agriculture at the University of Wrocław, where she obtained her master’s degree in 1951. She was hired as an assistant at the newly established Wrocław University of Agriculture. For nearly 20 years, she conducted intensive research, teaching, and publishing work. In May 1960, she defended her doctoral thesis. Animal feed was her passion, and she dedicated much of her time to working in experimental fields. At the beginning of 1969, she decided to leave her job at the University; her decision had its origins in health problems and conflicts with colleagues, resulting from her refusal to accept the low standards of work typical of the socialist economy. She moved to Warsaw and found a job in the editorial office of magazines aimed at farmers. The following decade was filled with intensive editorial work and frequent field trips, during which she visited agricultural centres and various types of farms. Towards the end of 1981, Zofia took early retirement at just 55 years old. She also remarried to Jan Mertens (her first marriage to a fellow student quickly ended).

It was a time of radical change in Poland. The communist system had collapsed, which paved the way for publicly addressing issues related to Soviet repression. Zofia and her mother joined the Union of Siberians (Związek Sybiraków). After the premature death of her husband, Zofia—looking to find a new meaning in her life—became involved in helping Poles from across the eastern border. Initially, this included residents of Ukraine, and soon after, the descendants of Polish exiles to Kazakhstan from the 1930s. Together with a mother of victims of Stalinist deportations, she dedicated not only her time, all her energy, and connections to the cause, but also her wealth – her savings and the material compensation for property lost in Volhynia. As compensation, she received blocks of flats in one of the villages in Lower Silesia. Gradually, the renovated flats (40 in total) were occupied by families brought from Kazakhstan, whom Zofia also helped to settle in and find work, persistently overcoming various obstacles and often the indifference of her compatriots.

Zofia’s exceptional dedication, openness, and courage were only recognized and appreciated by society towards the end of her life. She received numerous honours and awards, including the highest Polish decoration—the Order of the White Eagle (2017).

The volume consists of two source texts of different nature. The first is a several-hour long interview conducted by Małgorzata Ruchniewicz in the last year of Zofia Teliga-Mertens’ life. It fully covers Zofia’s biography.

The second text was written by Zofia herself. It was created 60 years ago as a competition entry. The author participated in the anniversary competition „We Grew up with the Polish People’s Republic”. The text was distinguished by the competition jury. However, it was not published because the author did not consent to censorship interference and the cutting out of fragments which she considered very important, including those related to her exile.

The typescripts of both testimonies and the recording of the interview in MP3 format are kept in the Research Archives of the Polish Ethnological Society in Wrocław in accordance with the will of their author (reference number 981/s).

Comments by admin